By Steve Carr

I went out a little later than normal for one of my runs downtown. It was a beautiful spring evening, just as the sun was setting. As I passed the local bus station, I observed something out of the ordinary. There was a group of taxi drivers gathered in the adjacent parking lot, kneeling on the ground. As I got closer I determined what they were doing: it was a group of Muslims on mats performing the salat—offering their evening prayers toward the east. I had never actually witnessed this on my run before and was even more surprised when I turned the next corner and saw more cab drivers praying on their mats.

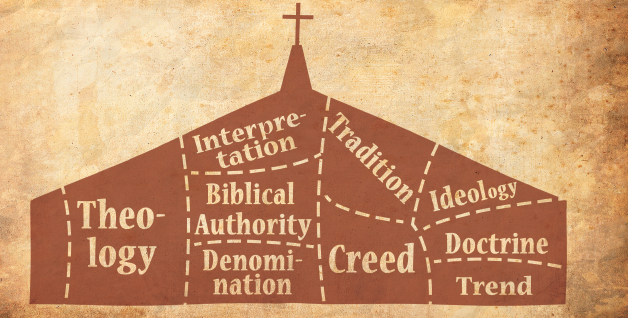

Of course Islam has existed for about 1,400 years, so evening prayers are nothing new. But the fact that the religion’s spread has become so pervasive that it’s regularly practiced in our medium-sized, Midwestern city definitely says something about the state of Christianity in our country—we are no longer the default choice of faith for Americans. This reality should galvanize Christians from different denominations into partnering together for the work of the gospel, but it hasn’t; there’s still an environment of jealousy and suspicion. It should make us ask: what is the true state of Christian unity?

Old-World Fractures

The United States was founded on freedom of religion. Those from many different Christian traditions flocked to America to carve out a future where they could practice their faith without repercussion. Soon, however, the religious atmosphere became one of contention. Religious leaders passionately argued that their theology was the correct one.

Even our own religious tradition, the Restoration Movement, which sought to simplify arguments by relying on biblical authority, was unable to escape debate. (I mean that literally; our movement was defined by debates.) Even though one of our mottos is, “In essentials, unity; in nonessentials, liberty; in all things, love,” the quest for unity has been elusive.

Babel Reversed

The Scriptures call us to be people of unity. Let’s examine Pentecost, the day the church began. Acts 2 is often summarized by Peter’s plea for people to “repent and be baptized.” Obviously, that’s a critically important command, but our takeaway should be more robust.

The day started with the gospel being preached to a multitude of people from various cultural backgrounds. Miraculously they heard the message in their own languages from the lips of people who had never spoken them previously. The diversity of dialects was no match for the power of the Spirit. Unity prevailed.

The Pentecost event seems to have a connection with an Old Testament narrative. After the flood, the descendents of Noah gathered on a plain and began to construct a tower in order to make themselves famous. The Lord noticed that their unity would lead to destruction; their desire to become God’s contemporary needed to be stopped. It was there, at the Tower of Babel, that God confused their languages so that their misguided unity would be thwarted. It wasn’t until Pentecost, thousands of years later, that God reversed the curse of Babel and brought unity through the gospel of Christ. Our efforts at unity imitate this reversing of Babel as we humbly submit to Christ’s call.

Repairing Cracks

I was a middle child. Birth-order experts suggest that children born between two siblings tend to have peacemaking proclivities. It’s been proven true in my life. I’m always looking for opportunities to forge connections between people and groups that seem ideologically opposed to each other. We tend to resist reaching out to those who differ from us because we fear sacrificing our core beliefs; it’s understandable that we would prefer the safety of what we know when facing the risks associated with compromise. Our reluctance to do so, however, can prevent us from having some unforgettable experiences.

A decade ago a group of believers (including my wife and me) started a church in urban Cincinnati. One challenge of church planting in the city is securing a place to worship; rent for meeting locations can be expensive. As opportunities were sparse, our leadership team determined we should approach neighborhood churches to see if they would be willing to lease space for us to use on Sunday evenings. The first church we approached had a beautiful, 100-year-old building and agreed to help us out; our independent Christian church was started in a Disciples of Christ building. While the Disciples are part of the Restoration Movement, our branches have grown distant over the years because of differing theology. There’s usually little collaboration between our congregations.

While nearly all of us prefer to regulate potential variables to ensure that there are no surprises, unity forces us to relinquish complete control and trust others. An example of this is when our church collaborated with the Disciples congregation for a joint Easter worship service. I was fearful that something would be said that would conflict with our congregation’s core beliefs. Even though some things happened that I’d never advocate, none of our members lost their faith as a result. In fact, our members were encouraged to see that we could maintain our identity while joining those with whom we had differing opinions.

Critics that Divide

I was blessed to become friends with Russell, a minister at a large mainline denomination in town. His sect of Christianity has continued to move away from biblical submission over the years. However, Russell and his congregation have decided to be a remnant in their fellowship, staying grounded in God’s Word when others have fled. Even though we have some theological differences, the concepts that unite us are too many to ignore. His friendship has proven invaluable.

When you’re a Christian in an American city, you realize that there aren’t nearly as many believers to be found as there are in suburban or rural areas (my encounter with the praying Muslims illustrates this). As a result, it’s critical to seek unity with those outside our fellowship because there are usually too few in our tribe with whom to partner. Even though this sounds reasonable, there are some who prefer that we avoid this kind of unity.

During one of my sermons, I casually mentioned that I had been a guest preacher at Russell’s church. That night I received a concerned email from one of our members, asking to speak with me and our elders about an important biblical issue. This individual was incensed that I would speak in the pulpit of a different denominational church; this person was certain that I had compromised to the point of sin. Our leadership disagreed, and after a long conversation, the concerned individual decided to attend another church. The whole situation saddened me. It’s difficult to advocate for unity when there is always the potential for criticism.

A Movement Toward Unity

Are we truly united as Christians? The fear of losing our identity keeps us insulated. But that doesn’t mean we can’t change. Ask your church leaders if they’ve connected with pastors from other local churches. I’d encourage you to take steps toward unity whenever you can. Collaborate with parachurch organizations that bring together a variety of believers through common causes such as homelessness or poverty.

Start praying for other churches in your community that they will see success in their kingdom efforts. Jesus prayed that believers would be one just as he and the Father are one. We have a role to play in answering his prayer.

Steve Carr is Director of Advancement and Development at Cincinnati Christian University and minister at Echo Church in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Comments: no replies