By Pat Jeanne Davis

It wasn’t what I expected would happen when I first visited the United Kingdom with my English-born spouse and our two Anglo-American sons. My husband visited his home in Britain, and our family had a vacation as well. But additionally I acquired a deeper appreciation of my American heritage.

“Am I British or American?” asked both Thomas and Joshua. Our young boys, born in Philadelphia, have dual citizenship. We keep a few English traditions at home. We also observe American holidays and participate in a community Fourth of July parade—the flag carried at the head of the procession. This is followed by a picnic and topped off with a spectacular fireworks display on the Ben Franklin Parkway.

Over the years I’d acquired at least a fair amount of history on England’s rich, varied, and ancient past. John, my husband, always made a point of reminding me “the United States is quite young.” Additionally he and I have had many lively discussions on each country’s merits and contributions to the world. I was informed that we Americans should be thankful for many things that the motherland gave us—not the least of which includes our legal system based on the British Magna Carta.

I was certain I knew a good amount of America’s past when I left these shores with my family. After all I’ve lived in historic Philadelphia, the birthplace of America’s independence, for 45 years—a city visited by many from all over the world who come to see Independence Hall, Congress Hall, and Carpenters’ Hall (the meeting place for the First Continental Congress) and to have their picture taken before the Liberty Bell. But traveling to England gave me a greater awareness of our national and religious heritage too.

Rediscovering Church History

We went to Cheshire, England for a church conference where my husband was a speaker. The participants gave a history on the well-known nonconformists George Fox (founder of the Quakers), John Bunyan, Richard Baxter, and others. During the mid-1600s thousands of dissenters went into hiding or were imprisoned. John Bunyan wrote Pilgrim’s Progress while imprisoned. William Penn, the eventual founder of Pennsylvania, became one of the most active champions of the Quaker movement and Quakerism became an expanding force in Philadelphia and in America.

I began to understand better the experiences and religious purposes that led many early colonists to come to the New World. They had entirely separated from the Church of England and in so doing broke with the king. The English separatists sailing from Holland in 1620 came here in order to worship as they pleased. Later called the Plymouth Pilgrims, they had experienced the same religious intolerance as those in the mid-1600s. In the Mayflower Compact, the first government of the people and by the people in America was set up. This formed a precedent for the principles embodied later in the new state and federal constitutions of independent America. The Plymouth Pilgrims are forever enshrined in our nation’s history.

Discovering England

My husband was an excellent guide on our first trip abroad as a family. The boys were so excited when entering Warwick Castle and the Tower of London, eager to survey the various pieces of armor and implements of war used in ancient times. We toured the magnificent Salisbury Cathedral, Westminster Cathedral, stately homes, and royal gardens.

We visited Sulgrave Manor in Northamptonshire, home to the ancestors of George Washington. Old Glory flies together with Union Jack at the entrance. The Washington coat of arms is carved in the spandrels of the stone arch above the front porch. The mullets and bars design (stars and stripes) is believed to have inspired our own national flag. This modest Tudor house stands today as a permanent reminder of the special relationship between two great English speaking nations. Our guide informed us that “Colonel John Washington left England in 1656 to take up land in Virginia that later became Mount Vernon. Col. Washington was the great-grandfather of General George Washington. . . . A portrait in oil of General Washington hangs in the Great Hall.”

“Was George Washington English or American?” asked Thomas. Traveling to England has brought our two cultures together and expanded our sons’ horizons as well.

Appreciation of America’s History

A more recent trip in town with my family to Independence National Historical Park now has more meaning for us. Across the street from Independence Hall we watched—to the sounds of a beating drum—as Continental Army reenactors drilled in the art of marching and musket etiquette. Inside Independence Hall hangs a portrait of George Washington. “That’s the same picture we saw in England,” said Joshua.

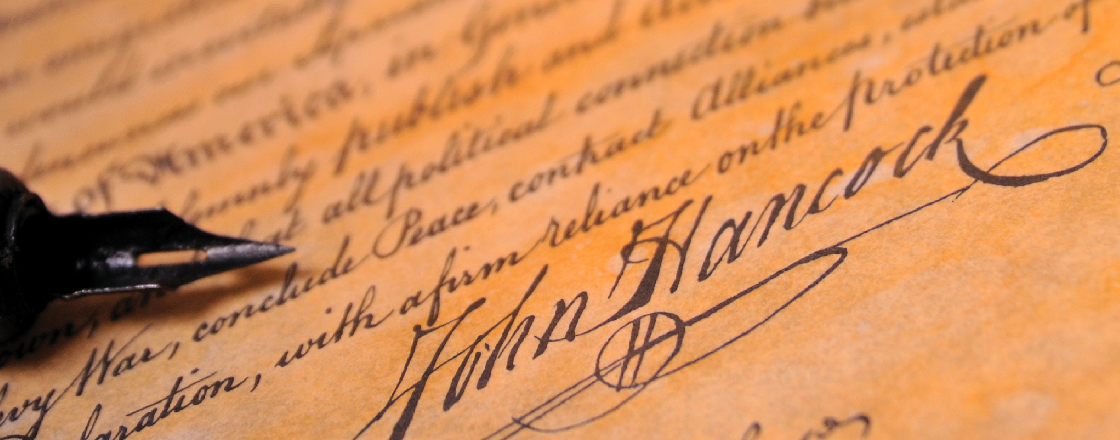

Our park guide spoke to us standing before a painting showing the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Here on July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress voted that the Declaration of Independence be adopted. This was the first great document in the history of a nation whose name would come to be a symbol of freedom to all the world. Its foundation was the theory of natural rights. The function of government was to make those rights more secure by means of laws having the consent of the governed. Within walking distance from Independence Hall and on a narrow cobblestone street sits the historic house that once belonged to Betsy Ross. A replica of the original stars and stripes flew in the warm breeze. Thomas remembered our visit to England. “There’s no Union flag here.”

“This wasn’t one of Philadelphia’s loyalist homes,” I tell him.

The birthplace of the American flag is alive with the sights and sounds of the eighteenth century. Outside characters in colonial clothes entertained us with a skit to the sound of fife and drum.

The boys and I walked around downstairs before ascending the narrow staircase to the top floor. Here in a replica of a colonial upholstery shop, my sons learned Betsy Ross’s fascinating history. Since my own school days when I first heard of her courage and how she’d triumphed over many tragedies, this worthy patriot had become a heroine of mine.

Our guide recounted some of this hardworking seamstress’s experiences after the death of four husbands. According to sworn affidavits by her family, in 1776 George Washington, Robert Morris, and George Ross, a member of the flag committee and the uncle of Betsy’s first husband, John, visited Betsy shortly after John’s death. General Washington pulled a folded piece of paper from his pocket. On it was a sketch of a flag with thirteen red and white stripes and thirteen six pointed stars. Betsy suggested changing the stars to five points rather than six and demonstrated how to do it with just one snip of her scissors.

This historical event became more significant as I recalled our first president’s connection to the Washington family of Northamptonshire, England and their coat of arms that inspired our stars and stripes.

Today I have a fuller understanding of America’s early history, the spiritual motivations of our ancestors, and the significance of my city. While our boys are learning of their own connection to England through their father, I also have the privilege of instilling in them a high regard for their American heritage and the place the City of Brotherly Love had in the founding of our nation.

Pat Jeanne Davis writes from her home in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Comments: no replies