By Steve Wyatt

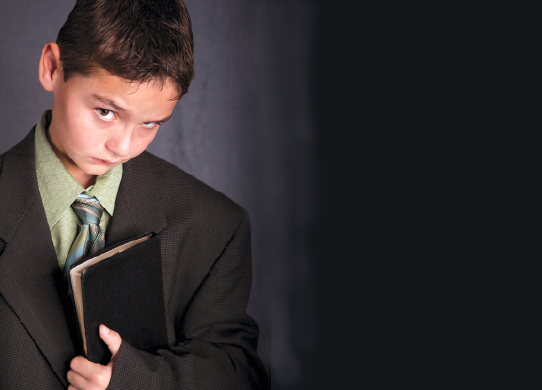

“Hello. My name is Steve and I’m a PK.”

It’s a chronic condition, this PK syndrome—and more widespread than many realize. Most of you reading this have either known a PK or perhaps you are a PK.

I write this confessional because I’m not my family’s only PK—my kids are also PKs. And my grandkids, too. Many of my nephews and nieces are also afflicted. Cousins, too—first and second, even a third (though I still have no clue how to trace that).

All I know is that in the Wyatt family, there’s a lot of diabetes—but even more PKs. Evidently the DNA for this condition runs quite deep. The Wyatts got overtaken a generation ago by this virus called (picture me feigning a furtive look over each shoulder, to the right and then the left, then slowly leaning in and whispering these words) “My dad is a preacher.”

There. I said it. He was. So is my kids’ dad. And now my beloved grandchildren have also been afflicted with the dreaded PK family condition.

No Whining

Perhaps you’re assuming this will be yet another “whine festival” from a wounded preacher’s kid who ranks his persecution right up there with Paul’s or who thinks his courage is equal to (if not greater than) Esther’s, who embraced her treacherous calling with, “If I perish, I perish” (Esther 4:16). If that’s what you’re bracing to hear, you’ll be disappointed. No whine fest from me.

I’m not saying I have no scars. Of course I remember many guarded conversations between Mom and Dad—who thought we couldn’t hear, but we did. I also remember leaving town under cover of night because dad had incurred the wrath of a ruling elder!

I could also moan about holidays jammed by church activities. And if having our holidays interrupted wasn’t enough, every Sunday—morning and evening—we PKs had to drop everything we’d rather do because we had to do church!

PK Volunteers

I don’t want to minimize PK pain. Truth is, PKs often get hurt. And the hurts leave scars. I have scars.

But here’s what I’ve learned about scars: scars are wounds that got healed. That you were wounded is obvious—because you’ve got a scar. But the scar means that you got better. You got over whatever happened.

The scars of PKs are real and the pain is often great. But if you allow your wound to steal your past, dominate your present, and obstruct your future, you’re not a PK victim; you’re a PK volunteer.

PK Stories

Here are some of my favorite PK stories. I hope they prompt other PKs to remember (maybe even with fondness) their own PK stories.

Do you remember “sword drills” in youth group and junior church? The teacher would shout, “Habakkuk 2:20!” and we raced to be the first to find it. Whoever did, stood up and read it. I still remember the first time I finally beat Kim Roush. That girl was good! We’re talking Amos 2 in under 3.2 seconds! So when I finally beat her, it was sweet!

Then there was the first song I ever sang in public. I was in third grade and my selection was “Trust and Obey” (hymn number 365 in Favorite Hymns of Praise, by the way). Talk about scared! I sang the first, second, and last stanzas with a walnut-sized lump lodged right in the middle of my throat! (I didn’t have to stand on the last stanza, though, since I was already standing!)

I also remember the many times my mom glared at me from the choir loft. Anybody remember choir lofts? Those holier-than-I’ll-ever-be songsters would sit up there in their flowing robes looking godly—a lofty position from which my mom could spy on my routinely bad behavior. Mom had a look that she’d flash at me. Whenever I got “the look” during church from Mom, I knew it would be hands-on after church with Dad!

Then there was the time Mom was in choir practice and my sister and I started fighting over gum. During the conflict I tripped over my stroller and cut a huge gash across my forehead. I’ve still got the scar to prove it.

I remember the old wooden pews in our West Virginia church. Every pew in the place bore cracks. So when it was time to stand for the invitation song (most often “Just As I Am,” hymn number 62 in Favorite Hymns of Praise), you’d better be the first one up, or that crack might just close with some of you still in it!

I got a million of ‘em! Like when our Boy Scout troop got busted for playing midnight football in the sanctuary. Or one hot, muggy afternoon when I took my buddies for a refreshing dip in the church baptistery. And when Joe, our youth minister, built a canoe in the third story catwalk of our very old church building—and couldn’t get it out!

Don’t Do the Dew

And then there was the incident that occurred soon after our church got its first soda machine. You could buy a Mountain Dew for 10 cents—but not on Sunday morning. I don’t know why. The only explanation we ever received had something to do with Sunday being the Lord’s Day and it wouldn’t be right to buy a Dew in the Lord’s House on the Lord’s Day. A rule I always believed was stupid—a rule that always made me extremely thirsty, especially on Sunday!

So one Sunday morning, Doug Briscoe and I sneaked out of Sunday school and got ourselves a Dew. We decided to drink it in the Benevolent Room (where they kept stinky old clothes to give to homeless people).

What we didn’t know was that Cora, the church secretary, was about to crash our impromptu party. And who did Cora grab by the ear and threaten to tell “your father”? Not Dougie. It was never the other guy. Just me, the PK.

Speaking of Dad, one Sunday night during Communion time, after my fourth service that day, I was goofing off—making fun of “Sleepy Williamson” by tossing spit wads and hoping to land one in his gaping mouth.

Dad saw me from way up on the platform; unfortunately, I didn’t see him see me. So near the end of the service, lights dimmed low, Communion being passed to the people on the front row (who hadn’t made it to any of the previous three services that day), dad slipped away from the platform, came around behind the back pew where I was sitting, and with those two meat hooks he called hands, grabbed me by the shoulders, lifted me up and over the back of the pew, took me into the coatroom, and provided a little wall-to-wall counseling—if you get my drift.

The craziest things that have ever happened to me happened to me at church. I can’t tell my best stories. You’d be disappointed in me!

For Every Cora, There’s a Katie

Some wonderful things have also happened to me as a PK. Take “Boots,” for example. Not the leather shoe. I’m talking about a second mom God gave me when my dad served a church in West Virginia.

Her given name was Beulah, though most everybody, including me, called her Boots. By the time I arrived, Boots Templeton already had five biological sons. But when this PK came along, Boots welcomed me with open arms and adopted me into her crowded family.

Through the years, Boots was a consistent reflection of godly love, a gift she passed on. Her oldest son, Myke, guided me through the most treacherous season of my life. Bruce became my longest and dearest life friend. Whenever I’m with Bruce, I think of Boots.

Boots went to Heaven a few years back and her sons invited me to sit in the pew with them at her funeral. As I sat there, I suddenly realized: Boots would’ve never known me if I hadn’t been a PK. Then I realized: Boots always loved me—not because of my condition; she loved me.

And that’s what I’m learning about this family “business.” For every Cora, there’s a Boots. Or a Katie.

Katie Hand witnessed the scolding I’d received during the Dew incident and found me sobbing on the back steps behind the church kitchen. She sat down beside me, hugged and consoled me, then shoved a quarter into my hand and said, “Your next Mountain Dew is on me. But don’t buy it till Cora goes home!”

Katie is also with the Lord, but during her lifetime she was a tireless encourager—to more than just me. In my blue file (a thick folder I turn to whenever I’m discouraged), I have dozens of notes from Katie. Many times she drove hours just to listen to me preach—even though it was physically taxing for her to do so. Knowing she was in the room always warmed my heart.

When I went through a tough patch a few years ago, Katie’s impact on my life really kicked into gear. I’m doing ministry today because folks like Katie never stopped believing in me.

A Syndrome with Benefits

So here’s the upside of my family condition. Katie and Boots (and many others) loved me—not because they thought I was special, but because they loved the church. And since my dad was the preacher who served their church, they thought Stevie was worth the investment—a smart-mouthed brat who grew up to do the same thing my dad did.

They never stopped investing and they never stopped loving. When others walked out, they’d walk in.

That’s a benefit I would never have known had I not been afflicted with PK.

So whenever I’m with my PK grandkids, I find myself praying for them and asking God two things:

Lord, don’t let these babies become yet another PK who sees in Papa or some ruling elder or a gossipy choir member or a surly church secretary any inconsistency that might become (for them) a reason to run or walk away from you. The inconsistencies exist—but protect them, Lord. And help them to see the passions that drive us. May they say of all of us that we dearly loved you and tried to overcome the hazards of this calling.

And Lord, would you also give them a Boots or a Katie? They will need to feel loved along this journey, so will you give them someone like those you gave to me?

Steve Wyatt is a minister and freelance writer in Anthem, Arizona.

Five Things You Need to Know About Preacher’s Kids

By Shawn Wuske, (grown-up preacher’s kid)

(1) If you want to find something in the church building, ask a PK. Mom and Dad only entered a room if it was serving a ministry purpose; I explored for the sake of exploring.

(2) If a PK seems to be uncomfortable around you, it’s probably not because his or her dad has an issue with you. When I was growing up, if my comfort level around a group of people would have been related to my dad’s, he wouldn’t have been nearly as effective ministering to Young at Heart groups as he was.

(3) Expect and allow PKs to make the same mistakes every other kid makes. Most PKs are aware that they’re in the public eye, but a congregation of people who criticize every mistake they make isn’t something any kid should have to endure.

(4) Don’t pressure PKs into becoming preachers themselves. Many PKs are also called to become ministers, but the last thing a kid needs is the added pressure of a well-meaning congregation trying to force a calling where no calling exists.

(5) If you expect your preacher to work 80 hours a week, you should also expect your preacher’s children to fulfill all the worst stereotypes of PKs. During my time as a youth minister, I saw how difficult it can be for kids to grow up without a caring, available dad. Don’t put your minister’s family in that situation.

Comments: no replies