By Joyce Long

“If I go and be a prostitute, I know I can make more money for my mother and my family,” said the Cambodian girl. The in-country social worker replied, “Yes, but when you are engaged to be married, that will lower your price.”

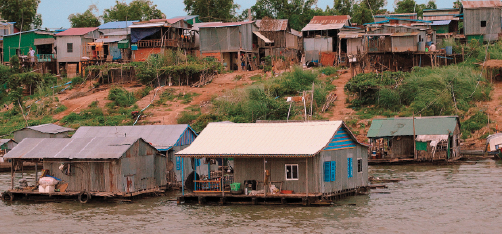

When Katy Beringer heard this, she sighed, realizing the complexity of culture among Southeast Asia’s impoverished families. “Because girls carry the burden of the family’s finances, there’s a lot of pressure. And if they live in a village, there are not too many opportunities to get work.” Katy and her husband, Alan, know too well how women in Cambodia struggle. They have served with Center for Global Impact (CGI), a faith-based, non-government organization, since 2011.

Customarily in Cambodia when a girl is betrothed, the groom’s family pays a dowry. Factors like education, purity, scars and bruises, and skin color determine the price. “If a girl burns her arm, she will worry about her price,” said Ryana DeArmond, CGI’s culinary training instructor. Ryana views human trafficking broader than it’s typically portrayed. “Some people think that human trafficking is being sold and taken across the border, but in reality, it’s any kind of exploitation.”

Cambodian children are considered minors until age 16. Parents living in extreme poverty may put pressure on their daughters, sometimes even younger than 16, to find work in places like beer gardens or karaoke bars, environments that breed sexual exploitation. However, those participating in illicit sex are sent off-site because if a third party is involved, prostitution is illegal in Cambodia. When the girls leave the premises, they are no longer on the clock at the bar. Often returning to work, they’re greeted with, “You’ve missed 20 hours of work this week so you owe us money.” Greater bondage follows.

International Vocational Training

Organizations like the International Justice Mission (IJM) train local police how to recognize trafficking and conduct rescues. However, the Cambodian government depends upon non-government organizations (NGOs) such as CGI to provide vocational training in the reintegration of those who have been exploited or are at-risk for trafficking.

Common Ground Christian Church (Indianapolis) has a heart for those victimized by trafficking and has supported the Beringers’ desire to work in Phnom Penh with CGI. As director of operations, Alan oversees CGI’s vocational training programs while Katy focuses on case management and curriculum for the Imprint Project. Both work closely with a partner organization, Destiny Rescue.

From Bluff City Christian Church (Tennessee), Ryana DeArmond oversees the staff of CGI’s two restaurants, Green Mango Café and Red Chili Mexican Grill. The Cambodian version of a food truck, the Taco Tuk Tuk, also provides culinary students another training and work option. After CGI students finish their culinary training based out of the Green Mango Café, they have the option of being paid to work at the restaurants.

In Battambang, Cambodia’s second largest city, only four other faith-based NGOs help reintegrate trafficked women. Ryana said that culinary arts and sewing, such as CGI’s byTavi program, are the two most commonly taught vocations. Other reintegration skills taught include hairstyling and tour guide training. The nation’s capital, Phnom Penh, provides more opportunities for at-risk women with approximately 30 NGOs offering vocational training.

Cambodian Education

Because of the Khmer Rouge genocide (1975-79), an estimated two million Cambodians, mostly professionals, were executed, leaving uneducated farmers to forge the country’s future. Since then, educational opportunities for Cambodians have been limited. Many cannot afford to send their children to school since they are needed to work in rice fields. Some simply cannot afford the mandatory uniforms. Newer programs, like CGI Kids, provide social workers to monitor student success and funds for school supplies, Bibles, and uniforms.

For dropout students, few opportunities exist for continuing education. “A 22-year-old must literally go back to fifth grade,” said Katy. CGI’s Imprint Project, located in Phnom Penh, offers an eight-hour school day, Monday through Friday, and teaches sewing to “girls who’ve chosen to leave a bad situation.” They are also taught mathematics, computer skills, Khmer language, and English. “If you can speak English, you can get a better paying job,” said Katy.

Imprint’s life skills curriculum teaches self-esteem, physical health, finances, and goal-setting. Time management, personal safety, and leadership skills are also covered. Participants study the Bible twice weekly. Culinary Training Center students receive similar training through their social worker. Ryana added that money management and personal finance seem to be difficult concepts for the girls to understand. “Everyone in Cambodia could benefit from that training.”

Reintegration Challenges

When working with exploited women, several challenges influence success. Katy struggles with “having faith that what we’re doing will help these girls the rest of their lives.” Alan added, “It’s difficult to see a girl leave the program for whatever reason because then we don’t know what she’s going to do next.”

Katy also believes Cambodian children still experience secondary post-traumatic stress disorder from their parents who lived through the Khmer Rouge. “For me, it’s the girls not seeing their potential,” said Ryana. “I have this saying that Cambodians have a ‘reset’ button.” It usually happens during the Khmer New Year when the girls return to their home province where negative influences overtake them.

The spiritual aspect also affects their success. “In Buddhism there’s a feeling of, ‘You get what you deserve,’ as in bad karma,” said Katy. During Pchum Ben holiday, they pray for the gates of hell to open so they can take offerings to the pagoda for their dead ancestors. “If they’re your parents, you have responsibility for them even after they’re dead. Holidays are hard enough in dealing with living relatives, let alone the dead ones. Only God’s love can provide them hope.”

Stripped Free

While CGI works in Cambodia with reintegrating exploited women, an Indianapolis initiative started by Kim Tabor reaches out to local sexually exploited women. Stripped Free began after Kim heard a friend comment during Bible study. Kim’s friend spoke up, “You all know I used to be a stripper, right?” After a few coffee dates and much prayer, that friend, Stefanie Jeffers, joined the faculty of Kim’s ministry, Finally Free. Later Kim and Stefanie began envisioning a segment of ministry that would help women who are working in strip clubs, and Stripped Free became a reality.

“It’s overwhelming to all the senses. Music is blasting. It’s dark except for the flashing lights. There are no windows. It’s very obviously a dark environment,” said Kim, describing the four strip clubs the ministry team visits every other week.

“Sadly just being in that environment is not the worst part of their lives,” said Stefanie. The girls have bills, child support, and frequently abusive spouses or family members. One girl supports her two children along with a niece and a disabled mother. “There’s a reality that keeps them there. They make a lot of money that they couldn’t make anywhere else,” said Stefanie.

During Stripped Free’s first month of ministry (April 2014), two dancers left the clubs and accepted Jesus Christ. “One girl danced Friday night, came to our Saturday night service, and never went back. The following weekend, which happened to be Easter, she was baptized,” said Kim. Reintegration begins by helping them make connections, find new employment, possibly pursue further education, and find a church.

Redemption and Hope

“Once the girls find out that Stefanie used to dance, it takes ministry potential to a whole new level. When she walks into these clubs, she’s a living, breathing billboard of hope for these girls,” said Kim. Stefanie left her job as a paralegal after a failed marriage, an abusive relationship, and a devastating miscarriage. She began to work in a club. “I lost everything in the three years I worked there—my house, my daughter. What made me decide to leave is that I honestly couldn’t take it anymore. It’s hard on your heart, your soul, and your body. It’s not glamorous at all.”

Fortunately Stefanie had a desire to return to Jesus Christ, whom she had known as a child. She wants the dancers to discover a deep relationship with Christ also. “Our bottom line is that every girl we come in contact with knows that they matter and Jesus loves them,” said Stefanie. Kim added, “But most of these girls have no concept of God. I’ve never been in an environment where it felt so spiritually dark and the light of Christ shines so brightly. We pray expecting a lot of women will come out of the clubs—sooner rather than later.”

To learn more about these ministries, visit their websites: www.centerforglobalimpact.org and www.taborministries.org. Check out their social media sites as well. For an overview about human trafficking, visit www.humantraffickingsearch.net or exoduscry.com or ijm.org.

Joyce Long is a freelance writer in Greenwood, Indiana.

Find Out More About Trafficking

Girls Like Us

by Rachel Lloyd

(HarperCollins, 2011)

Disposable People

by Kevin Bales

(University of California Press, 2012)

Not for Sale

by David Batstone

(HarperCollins, 2009)

The Slave Next Door

by Ron Soodalter and Kevin Bales

(University of California Press, 2010)

Terrify No More

by Gary A. Haugen and Gregg Hunter

(Thomas Nelson, 2005)

Half the Sky

by Nicholas Kristof and Sheryl WuDunn

(Vintage, 2009)

Comments: no replies